The tournament was played in San Sebastian, on the northern coast of Spain; it was ultimately won by Jose Capablanca, and famously so, for it was his first ever major international event, and thus his first time playing against many of the world's top players at the time.

Before we dive in, let's see the lineup of participants at this full and feisty fifteen player round-robin event:

- Amos Burn, aged 63. An ageing veteran of the chess world at the time, Burn of England was playing in tournaments long before newer players Rubinstein, Vidmar, Capablanca and Frank Marshall were even born. Back in his heyday during the 1880s and '90s he was competitive against contemporary masters Tarrasch, Chigorin and Schlechter. Although his last tournament was in 1912, he was still a force to be reckoned with throughout his career, and notably beat a young Alexander Alekhine in Karlsbad 1911, held later in the same year as San Sebastian.

- Dr. Siegbert Tarrasch, aged 49. While pursuing a career as a medical doctor, Tarrasch had long been established as one of the world's leading chess teachers and had a uniquely scientific approach to the game. Together with Steinitz, he was one of the first players in the late 1800s to recognize the importance of such concepts as the bishop pair, a space advantage and control of the center. Tarrasch greatly valued piece mobility, and his namesake opening, the Tarrasch Defense to the Queen's Gambit, perfectly represented his views.

- Richard Teichmann, aged 43. While never a contender for the world championship, Teichmann would go on to achieve his greatest tournament victory later this year in Karlsbad 1911 ahead of leading masters Rubinstein, Schlechter, Vidmar and Marshall. Notably, he was handicapped with only one eye, which had caused him trouble at some tournaments in the past.

- David Janowski, aged 43. An experienced Russian master, Janowski had a reputation for playing quickly and energetically, preferring to attack in open positions. He was held in high esteem by Capablanca, who noted that "when in form [he] is one of the most feared opponents who can exist". At the same time though, he was considered relatively weak in the endgame, and had dismal lifetime records against world champions Emanuel Lasker (+4-25=7) and Capablanca (+1-9=1). Still, he is one of only two people in history (along with Tarrasch) to have scored at least one win against each of the first four world champions.

- Geza Maroczy, aged 41. A long-lived Hungarian grandmaster, Maroczy was best known for popularizing the "Maroczy Bind", a classic formation with pawns on c4 and e4 (c5 and e5 for black). He was also well-known as a exceptional defender, and scored well against feared attacking players such as Frank Marshall (+11-6=8), Mikhail Chigorin (+6-4=7) and David Janowski (+10-5=5).

- Carl Schlechter, aged 37. A slightly lesser-known master from Austria-Hungary, Schlechter is perhaps most famous for coming within a hair's breadth of defeating Emanuel Lasker in their 1910 World Championship match. Going into the final game, Schlechter was leading by a point and needed only a draw to take the title. In a tense position with Lasker's king dancing around in the center, Schlechter blundered from a winning, to a drawn, and then tragically to a lost position, letting Lasker escape the match tied 1-1 with 8 draws. By the rules at the time, a drawn match meant the current world champion held the title and so, Schlechter narrowly missed out on his one and only attempt at the crown.

- Frank Marshall, aged 34. One of America's greatest chess geniuses, Marshall was widely feared as a cunning tactician and known for his aggressive playing style. His namesake opening, the Marshall Gambit in the Ruy Lopez, remains a popular weapon of choice for GMs even to this day! Since losing his 1909 match to Capablanca in surprising fashion, Marshall had advocated for the new prodigy to be invited to play in San Sebastian.

- Paul Leonhardt, aged 34. While never one of the strongest players in the world, over the course of his career Leonhardt was able to score beautiful wins against many of the world's elite players: Tarrasch, Tartakower, Nimzovitch, Maroczy and later Reti.

- Akiba Rubinstein, aged 29. Rubinstein was a Polish grandmaster widely considered to be among the strongest players never to become world champion. He was near the peak of his career in 1911 - just a couple years back he had tied for first with world champion Emanuel Lasker at St. Petersburg 1909, even winning his individual encounter with Lasker there. Needless to say, Rubinstein was one of the favorites to win this tournament, especially with the conspicuous absence of Lasker.

- Ossip Bernstein, aged 29. The Russian grandmaster Bernstein had an illustrious career and remained active in tournaments all the way into the late 1950s. While he was never quite in the same category as Capablanca or Alekhine, he achieved lifetime level or near-level scores against such great players as Emanuel Lasker (+2-3=1), Akiba Rubinstein (+1-1=7) and Mikhail Chigorin (+2-1=0). One of his best games was a brilliant win over Miguel Najdorf in Montevideo 1954, played when Bernstein was in his 70s!

- Oldrich Duras, aged 29. A little-known grandmaster from Czechoslovakia, Duras was part of the new generation that included Rubinstein, Capablanca and Marshall. He had been on the chess scene for barely a decade now, having scored one of his best results a few years prior at Prague 1908, where he finished tied for first with Schlechter, ahead of Rubinstein, Vidmar, Marshall and Janowski.

- Rudolf Spielmann, aged 28. The man, the myth, the legend, Spielmann was one of the last stalwarts of the old Romantic Era of chess, where swashbuckling gambits and dazzling sacrifices were the norm. He was certainly no stranger to launching his f-pawn as white, and excelled in creating complicated messes over the board where he could make full use of his unique imagination and creativity.

- Milan Vidmar, aged 26. A solid grandmaster from Slovenia, Vidmar's consistent tournament performances secured him a spot among the best players in the world for the first quarter of the 20th century, only topped out by Lasker, Rubinstein, Capablanca and Alekhine. In addition to being a chess player, he had a successful career as an electrical engineer, and later in life he became the president of the Slovenian Academy of Arts and Science.

- Aron Nimzowitsch, aged 25. While not at his peak yet, Nimzowitsch was without a doubt one of the most influential chess theorists of the early 20th century. He is best known for being one of the founders of the hypermodern school of thought, which argued that direct occupation of the center by pawns did not by itself secure an advantage and that controlling the center with pieces instead was a viable strategy. In later decades, this new way of thinking would ultimately give birth to the King's Indian Defense, the Grunfeld and also his namesake opening, the Nimzo-Indian Defense. All of these systems are widely played at the GM level today!

- Jose Raul Capablanca, aged 23. A newcomer to the elite chess arena, the young Capablanca was still riding the fame he received from demolishing the American Frank Marshall in their 1909 match with the startling final score 8-1 (excluding draws). This tournament was the child prodigy's first chance to test his mettle against the world's best players. Over the next decade, Capablanca would realize his full potential, ultimately dethroning Lasker in their 1921 World Championship match...

And now, we shall begin this exciting tournament with a look at the highlights from the opening round...

Round 1

The tournament started with a bang, having lots of excitement in the first round. Capablanca's first pairing was white against Ossip Bernstein, who reportedly had complained about Capablanca's admittance to the event! However, after receiving a sound thumping from the future world champion, the feisty Russian grandmaster kept his complaints quiet...

|

| Capablanca-Bernstein, San Sebastian 1911 (Round 1). Black to move. |

Earlier in the game, Capablanca had sacrificed two pawns to build a dangerous attack on the kingside, achieving menacing knights on f5 and h5. Although black's position is still defensible, Bernstein cracked under the pressure and erred with 25. ... Rh8?, allowing the forcing continuation 26.Re2! Qe5 27.f4!, driving black's queen away from the defense of g7. There followed 27. ... Qb5 28.Nfxg7! (D)

Black has little choice but to accept the sacrifice, and after 28. ... Nxg7 29.Nf6+ Kg6 30.Nxd7 white wins back the piece right away and maintains the attack. However, Bernstein's choice 28. ... Nc5? immediately collapses his position, moving a key defender away from the kingside. After the simple 29.Nxe8 Bxe8 30.Qc3, threatening mate on g7, Capablanca won in short order: 30. ... f6 31.Nxf6+ Kg6 32.Nh5 Rg8 33.f5+ Kg5 34.Qe3+ 1-0.

This surprising (to Bernstein at least) win spotlighted Capablanca as a rising star and he even won the tournament's brilliancy prize thanks to this victory! Not a bad way to start your first big super-tournament.

The other exciting encounter in the first round was between Maroczy, the esteemed defender, and Marshall, the esteemed attacker. In this spectacular battle, Marshall came just one step short of creating his own brilliancy:

|

| Maroczy-Marshall, San Sebastian 1911 (Round 1). Black to move. |

Marshall sacrificed a pawn for the attack, but Maroczy has defended in his typical resilient manner, and is just about ready to trade the queens off. Here, Marshall went for the tempting continuation 24. ... Qxg3? 25.fxg3 Rxg2+ 26.Kf1 Rdd2, creating the killer threat of 27. ... Rh2! with Rh1# to follow. However, Maroczy found the only way to defend: 27.Re4! and after 27. ... Bxe4 28.Qxe4 Rdf2+ 29.Ke1 Ra2 30.Kf1 (D) we reach a curious position

Black's rooks are powerfully doubled on the 7th rank, but it turns out that white can just barely hold out. Marshall first repeated moves with 30. ... Raf2+ 31.Ke1 Ra2 32.Kf1 and then tried 32. ... Rgf2+ 33.Kg1! (33.Ke1? Rh2! wins for black, when white must part with the queen to stop Ra1#) 33. ... Rfe2 and now 34.Qb1! unbelievably holds white's position together. Marshall found nothing better than a draw with 34. ... Rg2+ 35.Kh1 Rh2+ 36.Kg1 Rag2+ 37.Kf1 Rb2 38.Qe4! guarding the h1 square 1/2-1/2 38. ... Ra2 is met with 39.Kg1!, and the further 39. ... Rhb2 is answered with 40.Qe1!; in all cases, white avoids getting mated by the slimmest of margins.

Going back to the position where Marshall played 24. ... Qxg3?, he missed an incredible opportunity to put white into near-zugzwang with 24. ... g5!! (D)

White's pieces are utterly frozen. After 25.Qxf4 exf4 26.Rg4 Bc8 black wins the exchange, while 25.Rg4 is refuted by the spectacular 25. ... Rd1!! 26.Rxf4 Rxe1+ 27.Kh2 gxf4 when white will have to part with his bishop to avoid getting mated once black doubles rooks on the back rank: 28.Qxf6 Rdd1 29.Qf8+ Bc8 30.g3 e4! 31.Bxe4 fxg3+ 32.Kxg3 Rxe4 (D)

Despite white's numerous extra pawns, black's two rooks and bishop will outmatch the queen in this open position.

After 24. ... g5!!, 25.Rge3 Rxf2! 26.Qxf4 Rxg2+! 27.Kf1 gxf4 is also winning for black.

In the other games of the tournament, Janowski won a 161 move marathon against Duras, veteran Amos Burn drew with black against Carl Schlechter, and Vidmar successfully neutralized Spielmann's aggressive opening to also draw with black. Rubinstein achieved a large positional advantage against his elder rival Teichmann, but the latter found some ingenious defensive resources to draw a pawn down. Leonhardt sat out the first round, since there were an odd number of players.

Nimzowitsch suffered a now-famous defeat against Tarrasch, where he made an instructive blunder in a drawn ending:

Nimzowitsch suffered a now-famous defeat against Tarrasch, where he made an instructive blunder in a drawn ending:

|

| Nimzowitsch-Tarrasch, San Sebastian 1911 (Round 1). White to move. |

The position is drawn. After the simple 36.Kh7, stopping Tarrasch's threat of ...Rh8#, black cannot make any progress and would even have to be careful about white's idea of g2-g4-g5. However, Nimzowitsch instead played 36.Kh5?? and there followed 36. ... Rb5 37.Kg4 Rxf5 38.Kxf5 a5 39.Ke4 (D)

Nimzowitsch will be able to catch the a-pawn, and after playing g2-g3 black will not be able to win both of white's pawns on the kingside. However here Tarrasch reacted alertly with 39. ... f5+! and Nimzowitsch resigned in view of 40.Kd4 f4! when white will not get a chance for g2-g3. While white goes after the a-pawn, black easily mops up h4 and then g2 with his king, followed by queening the f-pawn.

Round 2

After the thriller of round 1, round 2 was more peaceful, with six of the seven games ending in draws before move 35! Amos Burn played safely to make a draw with white against Maroczy, while Dr. Tarrasch was unable to get any advantage as white against Schlechter. Rubinstein had no trouble equalizing with black against Vidmar, and after many exchanges the two agreed to a draw on move 22. Teichmann was the odd man out this time and could easily have fallen asleep watching some of these games.

Capablanca's round 2 pairing was black against Marshall, the only player in the field he had any significant experience against (and vice versa). Marshall played an unpretentious Exchange Slav (1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.cxd5) and after the queens were exchanged on move 9, Capa, who already was developing a reputation as an endgame virtuoso, began to slowly outplay Marshall and even won a pawn:

|

| Marshall-Capablanca, San Sebastian 1911 (Round 2). White to move. |

Capablanca has won a pawn, but his structure is compromised on the queenside and he also badly lacks in development, with the Rh8 still not participating. Rather than retreating the attacked bishop on c4, Marshall correctly played the active 19.Ne5! and after 19. ... Nxc4 20.Nxc4 f6 21.Rb1 it became clear that Marshall would win his pawn back and easily be able to hold the opposite colored bishop ending. After exchanges on b6, the two agreed a draw on move 32.

Janowski was able to reach a promising position on the white side of a isolated queen pawn ending, resulting from the Tarrasch Defense:

|

| Janowski-Nimzowitsch, San Sebastian 1911 (Round 2). White to move. |

White is clearly better because of the permanent weakness of black's d5 pawn and the ability to use d4 as an outpost square. However, endgames were not the Russian master's forte, and he played imprecisely to even let black accumulate a small advantage later on before making a draw on move 33.

This is a typical structure that arises from Tarrasch's patented defense - 1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 c5 4.cxd5 exd5 5.Nf3 Nc6, which very often leads to black having an IQP after a later dxc5:

Opening-wise, this was one of the most important theoretical positions back in 1911! For a while, black was scoring decently by using his superior piece activity to compensate for the weakness on d5. White would regularly take on c5 and then play e2-e3, developing the light squared bishop to e2 or d3 where it would either be passive or block the d-file for white's major pieces to attack the d-pawn. But in 1908, fortunes would change: Rubinstein and Schlechter were among the first masters to try fianchettoing the bishop with g3 and Bg2, which turned out to be a much stronger development. White's king was safe behind this formation, and from g2 the bishop would forever gaze at the weak d5 pawn, while white was free to coordinate his major pieces on the d- and c-files.

This new system was very successful, and to this day the kingside fianchetto remains the default setup for white against the Tarrasch, and the sole reason why it is now rarely seen in modern grandmasters' repertoires.

Despite the numerous draws, there were still a couple dramatic fights in round 2. Duras had a lucky escape with black against Leonhardt, with the Czechoslovakian grandmaster reaching a precarious position out of the opening with his king on f6!

|

| Leonhardt-Duras, San Sebastian 1911 (Round 2). White to move. |

Here Leonhardt could have put the game away with 21.Bc3+! bxc3 22.Qxc3+ Ke7 23.Rad1 with a crushing attack. Instead, after 21.Rfd1? black liquidated material with 21. ... Nd4! and after 22.exd4 Bxd5 23.Qe3 Bxf3 24.Qxf3 cxd4 white was unable to generate any attack and had to be content with a draw on move 32.

The only decisive game this round was Bernstein's win as white against Spielmann:

|

| Bernstein-Spielmann, San Sebastian 1911 (Round 2). Black to move. |

Spielmann is trying to make something out of his advanced pawn on c4, but should have been cautious of his queen's vulnerable placement on the e-file and a2-g8 diagonal. 21. ... Qf7 would have maintained his position, but he instead blundered a pawn: 21. ... Rc7? Planning to double on the c-file, but he missed 22.Nxc4! with the point that 22. ... dxc4? 23.Bxc4 wins the queen. After 22. ... Ne4 23.Nxb6 Qxb6 24.Bf3 Spielmann had lost the pride and joy of his position - the pawn on c4 - and went down in flames after trying a desperate pawn storm on the kingside.

Round 3

In round 3, the action was back, with three out of seven games being decisive. After beating Bernstein in round 1 and drawing with Marshall in round 2, the young Capablanca was already leading the field with 1.5/2 along with Tarrasch and Janowski. In his next game, we saw the battle of generations, with the 23 year old Capablanca playing white against the 63 year old Amos Burn. The hardened veteran tried his best to contain the new star, but by move 17 was already in a difficult situation:

|

| Capablanca-Burn, San Sebastian 1911 (Round 3). Black to move. |

Capa has the bishop pair, and to make matters worse, black lags in development and has to find some way to deal with the pressure against b5. Burn was unable to solve all of his problems in this position, and after 17. ... b4?! Capa simply picked up a pawn with 18.cxb4 Bxb4 19.Bxf6 Qxf6 20.Qe4, double attacking b4 and h7. The game continued 20. ... Bd6 21.Qxh7+ Kf8 22.Nh4 and Burn decided to try his luck in the pawn-down endgame after 22. ... Qh6 23.Qxh6 gxh6 (D)

We have opposite color bishops, but black's pawn minus and shattered structure mean this is practically hopeless to defend. Capablanca was in his element and duly converted the advantage, winning on move 46.

That win put Capablanca at 2.5/3, and meant that Tarrasch and Janowski would need to also win to keep pace with him. Unfortunately, Janowski found himself on the wrong side of a powerful attack in his game against Schlechter and was brutally crushed in just 27 moves. Tarrasch was on the back foot right out of the opening playing black against Maroczy, and after stubborn defense found himself in a difficult rook and pawn ending:

|

| Maroczy-Tarrasch, San Sebastian 1911 (Round 3). White to move. |

Tarrasch's pawn is one step away from queening on h2, but will he then be able to stop white's connected passers on the queenside? Maroczy could have won by a single tempo after 44.Ka6! h1=Q 45.Rxh1 Rxh1 46.b5 Kf4 47.b6 Ke5 48.b7 Rb1 49.Ka7 Kd6 50.b8=Q+ Rxb8 51.Kxb8 Kc6 52.a6. Instead, he played a move which he thought was equally good, 44.Kc6? (D)

White wins after 44. ... h1=Q+? 45.Rxh1 Rxh1 46.b5, just as in the 44.Ka6! variation. But Tarrasch, ever so precise in the endgame, spotted the problem with the king being on c6 instead of a6: 44. ... Rc1+! 45.Kb6 Rc4! threatening ...Rh4 and ...Rxb4+. The game ended in a draw after 46.Rxh2 Rxb4+ 47.Kc5 Ra4! 1/2-1/2

After 44. ... Rc1+!, if white had instead tried 45.Kb5!?, then he is one crucial tempo short of winning after 45. ... h1=Q 46.Rxh1 Rxh1, compared to if his king already stood on a6 here. This gives black enough time to come back with the king and secure the draw.

Teichmann obtained a clear advantage with white against Vidmar, but the Slovenian grandmaster put up a good defense and slyly offered a draw in a worse position, which Teichmann accepted. The encounter Spielmann-Marshall was a hard fought game between two skilled tacticians which also ended up drawn.

Rubinstein was skillfully outplaying Bernstein with the bishop pair and a space advantage, but in the critical moment the Polish star went wrong and missed a win:

|

| Rubinstein-Bernstein, San Sebastian 1911 (Round 3). White to move. |

Bernstein has sacrificed a piece for a speculative chance at perpetual, and the game ended here with 41.Kb3? Qc3+ 1/2-1/2. 42.Ka4 Qa5+ 43.Kb3 Qc3+ repeats the position, while 42.Ka2?? would even win for black after 42. ... Qxc4+ 43.Kb1 Qb3+ 44.Kc1 Bg5+!, and white must part with his queen.

There is a very instructive win here though, by giving back the piece: 41.Kb1! Qe1+ 42.Kc2! Qc3+ 43.Kd1 Qxa3 (D)

Black has regained the piece, but now it is white's turn to attack: 44.Qe8+, and black's king will be mated in short order: for example 44. ... Bd8 45.Qxe6+ Kb8 46.Qd6+ Bc7 (46. ... Ka7 47.cxb6+ or 46. ... Kc8 47.Bg4+ Kb7 48.c6+ wins the loose queen on a3) 47.Qf8+ and mate on a8.

For our last game in round 3, Leonhardt comically trapped his own queen mid-board against Nimzowitsch:

|

| Nimzowitsch-Leonhardt, San Sebastian 1911 (Round 3). Black to move. |

The position is equal; white has some prospects for a kingside attack, but the exchange of three minor pieces mean that black should be able to defend easily enough. Almost any move here is fine for black, e.g. Qe7 or Rdd8. Instead, Leonhardt played 28. ... Qd4?? and one cannot imagine the embarrassment he must have felt after 29.Nd5! (D)

Ouch. There is no defense to c2-c3, when the queen on d4 is out of squares. Leonhardt desperately tried 29. ... Rxd5 30.c3! Qxd3 when he simply found himself down a rook after 31.exd5! Qxc4 32.dxe6 and resigned a few moves later.

And so, already after three rounds, the young Capablanca is leading the field in his first super-tournament, with 2.5/3! Tarrasch and Schlechter are close behind, at 2/3.

Round 4

Round 4 was a good day for the theoretical endgame textbooks! Frank Marshall had to defend the classic rook and bishop pawn draw against Akiba Rubinstein:

|

| Marshall-Rubinstein, San Sebastian 1911 (Round 4). White to move. |

Modern day endgame theory tells us that this position with the split pawns should be drawn, although the defense is not trivial. Marshall played accurately here: 51.Kb3 Rb4+ 52.Kc3 Kb5 53.Rb8+ Ka4 54.Rc8! (D)

Importantly preventing the advance ...c5-c4, after which white would simply capture, and after trading rooks black will be unable to win with just the a-pawn. After the further 54. ... Rb3+ 55.Kc2 Rb5 Marshall was able to hold without too much difficulty. While mainly having a reputation as a strong attacker, Marshall was no slouch in the endgame either; although, he was not quite at the same level as Capablanca or Lasker.

Another fundamental endgame was seen in Burn-Spielmann:

|

| Burn-Spielmann, San Sebastian 1911 (Round 4). Black to move. |

Spielmann had played the opening quite rashly. The ageing British master showed his class with a punishing exchange sacrifice and was completely winning by move 20, having enormous pressure against Spielmann's king. After resilient defense, the romantic stalwart miraculously escaped into an inferior rook and pawn ending and was very close to a draw.

In the diagram, black is just barely able to hold on by keeping his rook active, e.g. 62. ... Re1. After 63.Kxc6 Kb8! black draws by keeping the king on the short side, and using the long side to give checks with the rook.

Instead though, Spielmann played the losing move 62. ... Re7?, and Burn could have achieved his well-deserved win by 63.Rg8+! Kd7 64.Kb7! (D)

Now black's king will be pushed to the long side! White is simply planning Rg8-g6-xc6 when black's king is on the wrong side of the board for a draw. 64. ... Re1 65.Rg7+ Kd8 66.Kxc6 Re6+ 67.Kb7! and white will ultimately be able to reach a Lucena position.

However, Burn blundered in return! Perhaps already dejected that he had been unable to put the game away earlier, he went for 63.Rxc6+? Kb8! 64.Rh6 (D)

It looks like black is in trouble: e.g. 64. ... Kc8? 65.c6! Re8 66.Rh7! and white will win by switching the rook over to a7. But here Spielmann found the only way to draw: 64. ... Rb7+! 65.Kc6 Rc7+ 66.Kd6 Kb7 and after 67.Rh8 Rc6+ 68.Kd5 Rg6 69.Rh7+ Kc8 1/2-1/2 we have Philidor's drawn position. A very narrow escape by Spielmann, who was one step away from defeat for most of the game.

Nimzowitsch, always the ambitious player, tried hard to win with black against Duras, even attempting a risky exchange sacrifice in the ending; nevertheless, Duras played well and that game ended up drawn. Leonhardt and Schlechter played a quick 18 move draw that saw some brief fireworks before mass exchanges led to an equal position.

Janowski made an instructive mistake against Maroczy that I believe is typical of over-aggressive players:

|

| Janowski-Maroczy, San Sebastian 1911 (Round 4). White to move. |

Black has just played ...b7-b5, and white could achieve a comfortable advantage with the typical maneuver 20.b4! followed by Nf3-d2-b3-c5. However, such positional approaches never appealed to Janowski, and he instead played for a speculative attack: 20.h4?! - this completely misses the requirements of the position. Black has no weaknesses on the kingside, and the exchange of two minor pieces leave white with limited firepower for an attack. Maroczy defended coolly and ended up winning the pawn on c3, and later the one on d4 as well. Janowski was unable to break through black's defenses, never even getting to play a single check. 0-1.

One of the shortest games in the whole tournament was also played in round 4, with Teichmann incredibly losing on time after just 14 moves against Bernstein! Apparently, Teichmann had somehow confused the time control for the event, which was 15 moves for each hour.

Of course one of the most anticipated encounters this round was Capablanca playing black against Dr. Tarrasch. This was their first time crossing swords over the chessboard and Tarrasch, more than 20 years Capa's senior, no doubt was curious to see what this rising star was really capable of. Tarrasch played very much in his own style, going for a middlegame where he had an isolated pawn: 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Bc5 4.c3 Nf6 5.d4 exd4 6.cxd4 Bb4+ 7.Bd2 Bxd2+ 8.Nbxd2 d5 9.exd5 Nxd5 10.Qb3 Nce7 11.0-0 0-0 12.Rfe1 c6 13.a4 Qb6 14.Qa3 Be6 (D)

|

| Tarrasch-Capablanca, San Sebastian 1911 (Round 4). White to move. |

At the time this was a popular opening system for white, but modern theory considers black to be doing perfectly fine. Capablanca has excellent control over the d5 square, and has no weaknesses in his position. Tarrasch rocked the boat here a little with 15.a5!? gaining space, but also weakening the b5 square. After 15. ... Qc7 16.Ne4 Rad8 17.Nc5 Bc8, white looks active, but black has gotten his rooks centralized and still has no problems. In fact, after the further 18.g3 Nf5 19.Rad1 Nd6 20.Bxd5?! Nb5! 21.Qb4 Rxd5 (D), Capa was even slightly better:

Black now enjoys playing with a bishop vs. knight, the d4 pawn is becoming a target, and white has some long-term weaknesses on the kingside light squares thanks to g2-g3. Capa pressed on, but Tarrasch played resolutely, going for a well-timed counterattack to avoid drifting into a much worse position. The game was ultimately drawn on move 38.

Heading into round 5, Capa still leads the pack with 3/4; Tarrasch, Schlechter, Bernstein and Maroczy are all close behind at 2.5/4.

Round 5

The final round we will look at today saw some of the hardest fights in the tournament so far. Here were the matchups:

- Capablanca (3) - Janowski (1.5); Janowski had lost his last two games and was clearly out for blood against the young Capablanca.

- Maroczy (2.5) - Leonhardt (1)

- Rubinstein (2) - Burn (1.5); another battle of the generations

- Schlechter (2.5) - Duras (1)

- Spielmann (1.5) - Tarrasch (2.5); how would Tarrasch fare as black against such a daredevil tactician?

- Teichmann (1) - Marshall (2)

- Vidmar (1.5) - Bernstein (2.5)

Capablanca would have to deal with the wounded but always dangerous Janowski, while if Maroczy, Schlechter, Tarrasch or Bernstein won they could easily rise towards the top of the pack. This one was a thriller: all but two of these games were decisive!

Rubinstein exchanged queens on move 5 against Amos Burn and although he had slightly more active pieces in the resulting endgame, he was unable to make anything of it and the Englishman staunchly held a 46 move draw.

Tarrasch played the solid French Defense against Spielmann, trying to avoid the tactical wizard's favored Vienna Opening (1.e4 e5 2.Nc3), where white often plays an early f2-f4 to attack. However, that didn't stop Spielmann and he built an aggressive setup regardless. After many piece exchanges the players reached the following position:

|

| Spielmann-Tarrasch, San Sebastian 1911 (Round 5). White to move. |

Tarrasch has bagged a pawn, but Spielmann's excellent control of the dark squares offer a lot of compensation. After 30.Qd4 Qc7 31.f5!? the game liquidated to equality: 31. ... exf5 32.Qxd5+ Rf7 33.Nxd7 Qxd7 34.Qxd7 Qxd7 35.Rxd7 Rxf5 and the players agreed to a draw a few moves later.

So only managing a draw, Tarrasch was unable to make progress towards the tournament leaders. Maroczy fared even worse; in a roughly even position he inexplicably blundered the exchange:

|

| Maroczy-Leonhardt, San Sebastian 1911 (Round 5). White to move. |

After the natural recapture 18.Rxf3 Qe7, the game is roughly level. For whatever reason, Maroczy decided on 18.gxf3?, allowing the straightforward 18. ... Bh3. On 19.Rf2 Qh4! skewers the bishops along the 4th rank: 20.Qc1 Bb6 and black wins material. Maroczy tried 19.Qg3 Bxf1 20.Rxf1 (20.Bh6 Bxe5!), but Leonhardt consolidated and went on to win.

Bernstein played the rare Sicilian Defense against Vidmar, and after a wild king walk he had even managed to win a pawn. However, much like in his game against Capablanca, at a critical moment he cracked under pressure:

|

| Vidmar-Bernstein, San Sebastian 1911 (Round 5). Black to move. |

Just by looking at this position, you wouldn't think that anything too extraordinary happened, but believe it or not black's king made the journey g8-f8-g7-f6-e7-d7-c7 and then back again: c7-d7-e7-f8-g7-g8 to arrive where it is now. During the course of those adventures, white sacrificed a pawn but was unable to deliver a knockout blow...up until Bernstein's blunder here: 41. ... Qg4?? 42.Rd8! and black resigned in view of 42. ... Rxd8 43.Rxd8+ Kh7 44.Qf6 Rc1+ 45.Kh2 with unstoppable mate on h8. After the correct 41. ... Qf5!, black would have nothing to fear from 42.Rd8 Rxd8 43.Rxd8+ Kh7 since the f6 and e5 squares are defended.

Frank Marshall ground down Richard Teichmann in a long 76-move endgame. Only Schlechter from the 2.5 point group was able to win this round, playing a superb game against Duras:

|

| Schlechter-Duras, San Sebastian 1911 (Round 5). White to move. |

Duras has played the opening rather passively, and Schlechter punished this vigorously with the strong piece sacrifice 10.f4! Bxc3 11.bxc3 d5 12.Bb3! f6 13.fxe5! fxg5 14.Rxf8+ Kxf8 15.Qf3+ Kg8 16.Rf1. After the further 16. ... Nd7 17.Qf7+ Kh8 18.exd5 cxd5 19.Qf8+ Qxf8 20.Rxf8+ Ng8 21.Nf3 Be6 22.Rxa8 Nxa8 23.Nxg5 Nc7 24.Nxe6 Nxe6 25.Bxd5 (D):

The players reached this endgame after a long semi-forced line. White is much better, with a strong bishop and three pawns for black's two clunky knights. Schlechter went on to win in 43 moves, thus bringing him to 3.5/5.

And last but certainly not least, we have one of the most critical games of the entire tournament: Capablanca's battle with Janowski. The aggressive Russian master was licking his wounds after losing twice in a row to Schlechter and Maroczy. If he could beat the newcomer Capablanca, the tournament standings would be completely mixed up, with Schlechter ending up as the sole leader at 3.5/5! Likewise, if Capa could win, he would maintain his sensational momentum as the tournament leader. After 24 moves, the players reached the following position:

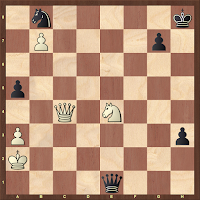

|

| Capablanca-Janowski, San Sebastian 1911 (Round 5). Black to move. |

The opening and early middlegame was relatively quiet, but the tension had been building over the last several moves, with Capablanca moving his pieces towards the queenside to try and win the weak b6 pawn, while Janowski has been keenly eyeing the kingside. On his last move, Capa captured a knight on c4 with his bishop, and rather than make the reflexive recapture 24. ... dxc4, Janowski went for the classic bishop sacrifice: 24. ... Bxh2+! 25.Kxh2 Qh4+ 26.Kg1 Qxf2+ 27.Kh2 Qg3+ 28.Kg1 dxc4 29.Qc2 (D)

Black has sacrificed a piece, but he is getting quite a few pawns for it. At the very least, Janowski has a perpetual check, so it seems like Capa's chances to win here are slim to none. However, that is not taking into account the fact that Janowski most certainly wasn't content with a draw...

The game continued 29. ... Qxe3+ 30.Kh2 Qh6+ 31.Kg1 Qe3+ 32.Kh2 Qg3+ 33.Kg1 Qe1+ 34.Kh2 Nf6 35.Nxe6 Qh4+ 36.Kg1 Qe1+ 37.Kh2 Qh4+ 38.Kg1 Ng4! 39.Qd2! Qh2+ 40.Kf1 Qh1+ 41.Ke2 Qxg2+ 42.Kd1 Nf2+ 43.Kc2 Qg6+ 44.Kc1 Qg1+ 45.Kc2 Qg6+ 46.Kc1 Nd3+ 47.Kb1 fxe6 (D)

After the barrage of checks we reach a position where Capablanca's king has escaped to relative safety, but Janowski has collected four pawns for a piece and still has a powerful knight on d3 to make threats with. At first glance it seems that only black can be better here, but things are not so simple! The pawn on b6 will likely fall, and then Capablanca's b5 pawn will become a real threat. All three results were still very much possible at this point in the game.

From here, things continued 48.Qc2 h5! Janowski wastes no time in getting his h-pawn rolling. 49.Bd4 h4 50.Bxb6 h3 51.Bc7 e5! 52.b6 Qe4 53.Bxe5!? (D)

With his back against the wall, Capablanca makes a last-ditch attempt to muddy the waters. His point is that 53. ... Qxe5? allows 54.Qxc4+ Kf8 55.Qxd3, when white remains a piece up, although black certainly still has chances after 55. ... h2 56.Qf3+ Qf6. The knight cannot take on e5 right away because it is pinned to the queen. But Janowski saw that he could get the queen out of danger with tempo by playing a check on e1 or h1; however, only one of those squares would win for him! Unfortunately for the Russian master, he erred here, letting Capablanca right back into the game: 53. ... Qe1+? 54.Ka2 Nxe5 55.b7 (D) Had the black queen stood on h1, the pawn could simply be captured on b7 right now.

That b-pawn is proving quite dangerous! Black's queen cannot get back in time, so the only piece that can stop it now is the knight: 55. ... Nd7 56.Nc5 Nb8 57.Qxc4+ Kh8 58.Ne4! (D)

A picturesque situation and a good pattern to remember in queen and knight endings. Despite white's king being seemingly open to checks, Capablanca has all the squares covered! Janowski can neither use e2, d2 or f2 as a checking square, and furthermore there is the winning threat of 59.Qc8+ and 60.Qxh3+, picking up black's h-pawn with check. The best move for black is anything to guard h3: either 58. ... Qe3 or 58. ... Qh4!?, when 59.Qc8+ Kh7 60.Qxb8 Qxe4! gives black a good chance at perpetual check. In this difficult moment though, Janowski made his last blunder with 58. ... Kh7? which was answered with the precise shot 59.Qd3! (D)

After this cold shower, the tables are turned! On 59. ... h2?, the black king is hunted down: 60.Ng5+ Kh6 61.Nf7+ Kh5 62.Qf5+ Kh4 63.Qf4+ Kh3 64.Ng5+ Kg2 65.Qf3+ Kg1 66.Nh3#. Janowski tried 59. ... g6 but now 60.Qxh3+ picks up black's last hope of counterplay and after 60. ... Kg7 61.Qf3! once again controlling all the key squares, it became clear that Capablanca had things under control. The game ended quickly: 61. ... Qc1 62.Qf6+ Kh7 63.Qf7+ Kh6 64.Qf8+ Kh5 65.Qh8+ Kg4 66.Qc8+ 1-0 Forcing the exchange of queens, when white will promote to a new queen.

This important win secured Capablanca's reputation as a true rising star, and served as a confidence booster for the future rounds of the tournament. After the first third of the tournament, we have the following standings:

- 4.0 - Capablanca

- 3.5 - Schlechter

- 3.0 - Marshall, Tarrasch

- 2.5 - Rubinstein, Vidmar (with one bye), Bernstein, Maroczy

- 2.0 - Nimzowitsch (with one bye), Spielmann, Burn, Leonhardt (with one bye)

- 1.5 - Janowski

- 1.0 - Teichmann (with one bye), Duras (with one bye)

So Capablanca is the leader, but only by a half point. Schlechter at his prime was a force to be reckoned with - after all, he did almost defeat Lasker in their World Championship match one year previously, and he had already won convincingly against Janowski and Duras in this event. In close pursuit are Marshall and Tarrasch, both seasoned and experienced fighters. Rubinstein and Vidmar both have had a slow start, but there are still ten rounds to go...

Rounds 6 through 10 will be covered in part 2.

Wow

ReplyDelete